APAC 2025

Singing Songs of Work and Pride

Channeling Woody Guthrie at APAC 2025

A single AP® course has enormous power to change a student’s trajectory for the better, and that sense of possibility was underlined with both data and personal stories in the second-day plenary of the 2025 AP Conference.

Trevor Packer, the head of the AP Program, emphasized during his annual briefing on the state of AP that convincing a student to opt into a single AP course can make a world of difference in college-going rates and college outcomes. “That’s where we see the strongest effect,” Packer said. “Finding those students who have none and bringing them to one.” Completing just one AP course during high school delivers a 16-point bump in college graduation rates, compared to a five-point boost for students who add a second course.

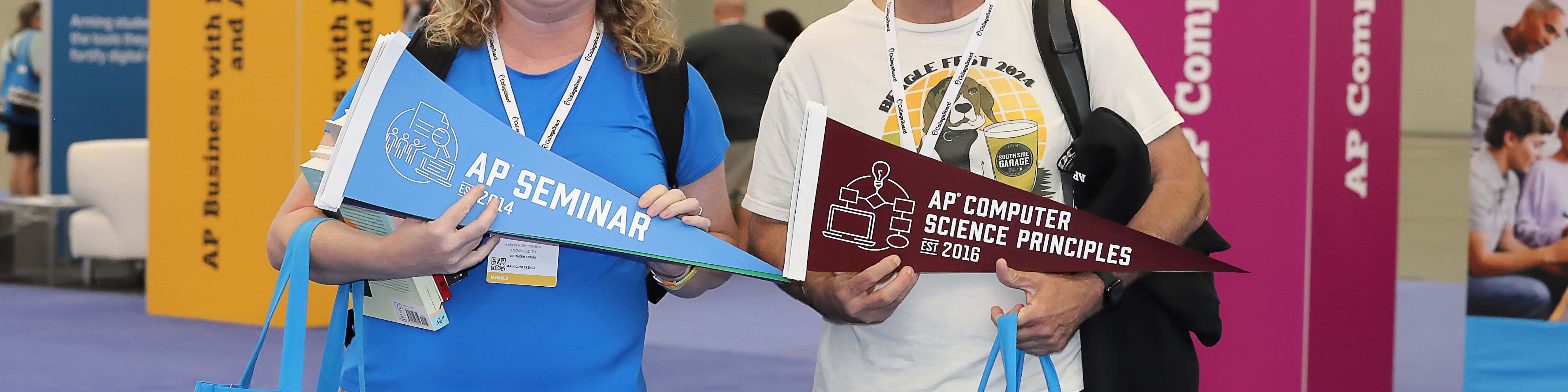

That is why so much of the AP Program’s effort in recent years has focused on reaching students who might not have considered themselves AP material. Courses like AP African American Studies, AP Precalculus, and AP Seminar can serve as inviting gateways to college-level work in high school, convincing students that they’re capable enough to succeed in higher education.

“Every one of us needs a friend, a mentor, a life coach who pushes us,” said Kelly Brouse, assistant director of pupil services for the West Hartford Public Schools in Connecticut. “When you’re in high school, all you want in the world is a sense of confidence about the future, and it’s powerful when a teacher cares enough to carry that confidence for you.”

Brouse took the stage to talk about her friend, mentor, and former teacher, College Board’s trustee chair Tom Moore. As a longtime educator and school administrator in West Hartford, Moore helped transform the district’s approach to advanced coursework, making college-level classes available to a much broader population of students.

He was also an advocate for students like Brouse, who knew she wanted to pursue college but didn’t think she could handle an advanced history course. “At every step, his confidence in me was boundless,” she said about Moore. “His confidence was the reason I came to love history,” to the point that she now reads biographies and historical fiction for fun.

Following Brouse on stage, Moore recalled his own journey from complacency about AP—assuming the courses were best reserved for the top-performing students—into a staunch advocate for wide access to advanced coursework. “We have to believe in them before we can expect them to believe in themselves,” he said, calling on teachers and school leaders to encourage students toward the most challenging curriculum. “The story of AP over the last 30 years is a story of choosing belief over doubt.”

Calling it a countercultural message, Moore said that students crave rigor because they want to know they can achieve at high standards. It’s the job of adults—parents, teachers, policymakers—to create those opportunities and set strong expectations. “If AP is going to keep making an impact for the next 70 years, it’s because the people in this room keep stepping up,” he said to a crowd of thousands of AP teachers from across the country. “It’s the story you write in the decisions you make.”

Moore rounded out the opening talk with a favorite quote from folk singer-activist Woody Guthrie, saying he used to give his students a poster of these song lyrics to carry with them to college and beyond. “I hate a song that makes you think that you are not any good,” Moore recited, quoting Guthrie. “I am out to sing the songs that make you take pride in yourself and in your work.”

With that sentiment hanging in the air, thousands of educators made their way out into the Boston Convention Center, bound for sessions about everything from neurodiversity in the classroom to Federal Reserve Data in AP Macroeconomics. “How lucky are we,” Moore asked, “that our jobs matter—tangibly.”